Is Demography Still Destiny After 2024?

Party coalitions change, but group ideological preferences are more persistent.

In winning reelection, Donald Trump lost the Hispanic vote by a much smaller margin than he and other Republican candidates lost it in the past. According to exit polls, Hillary Clinton won Hispanics 66–28 when she faced Trump in 2016, but this year Kamala Harris won the group by just 52–46. Contradicting the Republican National Committee’s 2013 “autopsy,” which claimed that the party needed to embrace amnesty as an outreach tool, Trump managed to attract Hispanic support while still taking a strong stand against illegal immigration. Party strategists will hopefully internalize this lesson.

Republicans should be skeptical, however, of another possible “lesson,” which is that they need not worry about the political effects of immigration. Hispanics are no longer a reliable Democratic voting bloc, as this argument goes, so fears that immigration will shift the political center leftward must be unfounded. This argument confuses ideology with party. The U.S. will probably always have two major parties, with each garnering the support of roughly half the country through coalition politics. The potentially transformative effect of mass immigration is therefore not that Republicans will disappear, but that they will weaken their traditional conservative ideology in order to stay competitive. Put more succinctly, many Hispanics could be Trump Republicans but not Reagan Republicans.

For a straightforward illustration of how voting groups can change parties without changing their basic ideology, consider 1988. That year Democrats suffered their third straight blowout loss in a presidential election. The party’s nominee, Michael Dukakis, managed to win only in progressive bastions such as Oregon, Massachusetts, and… West Virginia? Yes, today’s Trump-loving West Virginia was one of only 10 states that Dukakis, a liberal technocrat, managed to win in 1988.

What accounts for West Virginia’s rapid journey from blue to red? Few would argue that the state’s electorate has transformed. The same brand of economic populism and cultural traditionalism that we observe there today was also present in 1988. What has changed is the coalition of voters that each party recruits. Democrats still counted blue-collar union workers as a core constituency when Dukakis was their standard bearer, and social liberalism was less ascendant within the party at the time. Gradually, however, upscale voters concerned about environmental and social justice issues gained more influence among Democrats, while the Republican party’s economic appeals turned increasingly populist. West Virginia is now a natural fit with the GOP—not because the state’s voters changed, but because the parties changed.

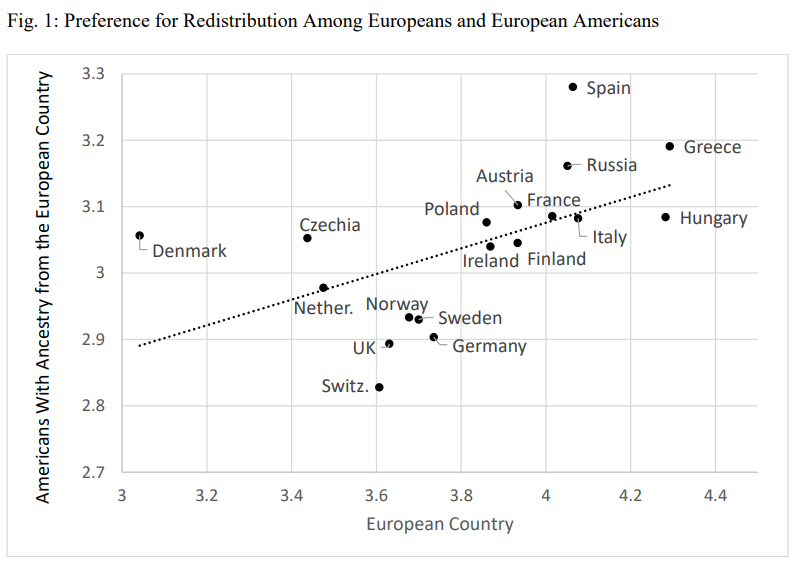

In maintaining similar political attitudes over time, West Virginians are hardly unique. Data show that group ideological preferences persist to a significant degree across generations, and those preferences appear to have deep cultural roots. My new working paper provides a good illustration. It compares the preferences for economic redistribution among Americans of European descent with the preferences for redistribution in their ancestral countries today. The correlation revealed by Figure 1 is remarkable:

Preference for redistribution is measured on a 1 to 5 scale, with 5 indicating the greatest preference. In Europe, represented on the horizontal axis, Italy has a greater preference for redistribution than Ireland, which in turn prefers more redistribution than the Netherlands. In the U.S., represented on the y-axis, the same order emerges—Italian Americans want more redistribution than Irish Americans, who want more redistribution than Dutch Americans. This relationship is present even among fourth–generation Americans, and it remains significant when controlling for age, education, income, and other demographic variables. The results imply that immigrants bring some of the values of the Old Country with them to their new homes, and then they partially transmit those values to their descendants. The economist Garett Jones calls this phenomenon “culture transplant,” and political preferences are a key aspect of it.

A recent study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics illustrates the transplant of political culture in a different way. It finds that when millions of white Southerners moved away from the old Confederacy to parts of the Midwest and West, they did not adopt the views of their new neighbors. Instead, they brought their conservative politics with them, eventually joining the Republican party in a Northern “New Right” coalition. Once again, the parties changed more ideologically than the voting groups themselves did.

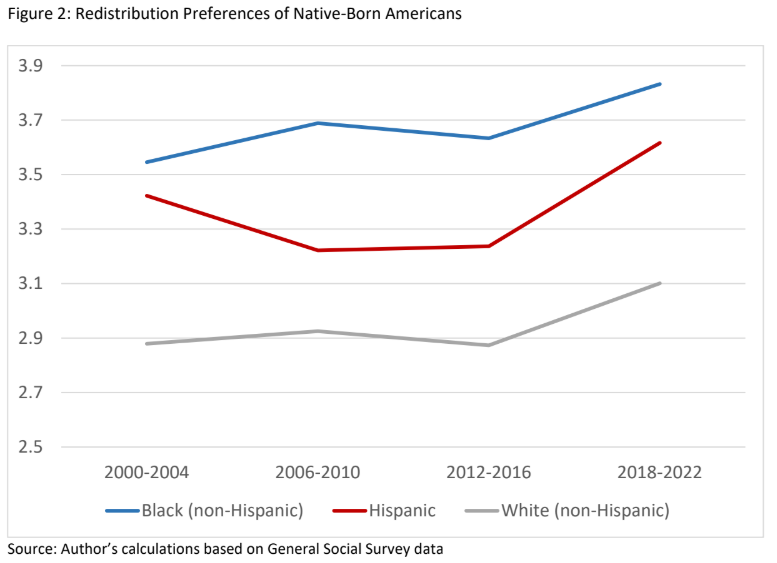

Given cultural persistence as a general phenomenon, the primary driver of increasing Hispanic interest in the GOP is unlikely to be these voters’ own ideological transformation. Although better data on long-term political attitudes among Hispanics are needed, a major turn toward conservatism is not yet evident. On the question of redistribution, for example, native-born Hispanics have consistently favored more of it than native-born non-Hispanic whites, with only modest relative changes occurring since the General Social Survey began identifying Hispanics in 2000. Figure 2 uses the same 1-5 scale as before, with 5 indicating the greatest preference for redistribution:

Furthermore, earlier this year the Pew Research Center asked a sample of U.S. adults whether the government “should do more to solve problems” or “is doing too many things better left to businesses and individuals.” While 70 percent of Hispanics said government should do more, just 44 percent of non-Hispanic whites took that position.

A better explanation for Republicans’ shrinking deficit with Hispanic voters is the same shifting party coalitions that produced West Virginia’s Dukakis-Trump voters. Republicans under Trump have de-emphasized free market economics in favor of more populist appeals on issues such as trade, entitlement spending, and even union support. Meanwhile, Democrats have increased their focus on social activism and lifestyle issues affecting educated professionals. It’s unsurprising that Hispanics, a predominantly working-class group not traditionally animated by social issues, are taking a greater interest in Republicans.

Evidence for these coalition changes comes in part from the resentments expressed by the old guard of each party. In announcing that he would not run for reelection during Trump’s first term, then-Senator Jeff Flake lamented that “a traditional conservative who believes in limited government and free markets” is less welcome in the modern Republican party. He later endorsed Kamala Harris for president. Shortly before this year’s election, National Review published “An Elegy for Reaganism,” wondering what happened to limited government as the GOP’s organizing principle.

On the other side of the aisle, senator Bernie Sanders is bitter as well. “It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working class people would find that the working class has abandoned them,” he argued. “First, it was the white working class, and now it is Latino and Black workers as well.”

Whether one favors the new party coalitions or instead shares the old guard’s distaste for them is not the issue here. The point is that the Democratic and Republicans parties do not represent static sets of principles. Instead, the parties are engaged in a dynamic ideological process—modifying their platforms, recruiting and shedding coalition partners, battling for control of the political center, always in search of 50 percent plus one. When voting groups move from one coalition to the other during this process, it is the parties that are more likely to have changed their ideological commitments, not the voting groups themselves.

Of course, there is a way to alter voter ideology in the aggregate, and that is to import new voters. The political impact of immigration remains very real—and very concerning, if one is a traditional conservative—because immigrants bring persistent values and beliefs that can shift the political center that each party is trying to attract. The coalitional changes discussed above suggest the impact is already being felt, as Republicans have downplayed free markets to accommodate working-class voters.

“Partly as a result of continued high levels of legal immigration, the percentage of the electorate that supports small-government conservatism is going to shrink,” concluded the political scientist George Hawley. The shrinkage could move America in a progressive direction, even as the Republican party remains alive and well.

The post Is Demography Still Destiny After 2024? appeared first on The American Conservative.